Volume 5 | Issue 12

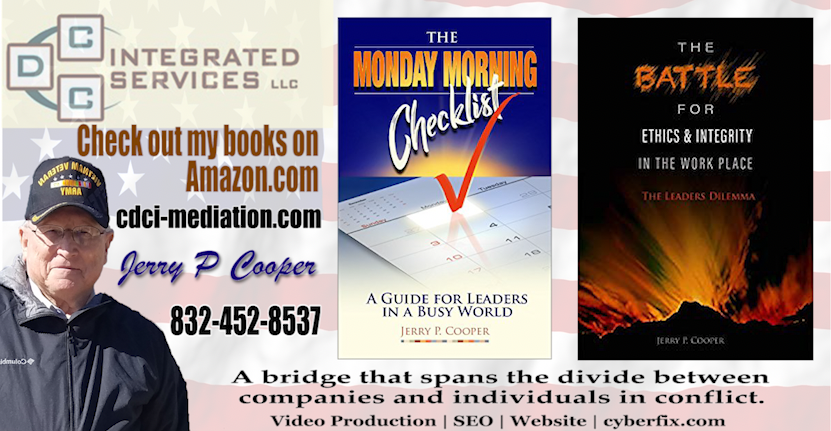

Putting it in contextA message from CDC Integrated Services, LLC

Resolving Conflict

Everyone has an opinion on resolving conflict. I am in the conflict solutions business so I also offer opinions. When I write about something, I am always conscious about the enduring truism about advice; it only worth something if it’s invited.

Everyone has an opinion on resolving conflict. I am in the conflict solutions business so I also offer opinions. When I write about something, I am always conscious about the enduring truism about advice; it only worth something if it’s invited.

My letters, not being offered in response to a specific request, are balanced carefully on that fine edge between “now that’s interesting” and “oh no, not again”. The purpose of my letter, Putting It in Context, is simple – to offer insight into an idea or concept that has practical application to those making critical decisions related to conflict in the workplace.

In previous letters, I talked about the conflict resolution triangle. It is an image I used to explain the process of separating the individual(s) from the issues through a three-part process where this separation process is the first part.

This is followed by the explanation part and this involves constructing the explanation that is the foundation of any negotiation of the issues. Only then do I guide the process through the process of developing the criteria in clear and concise terms for exploring solutions.

In summary, the three points of the triangle that I use in my process are Separate, Explain, and Identify. And it all begins by asking questions. If you don’t begin the conflict resolution process by asking questions, you will come to an abrupt standstill when you encounter the assumptions that the various parties built up in defense of this or that position. Entrenched assumptions are extremely difficult to dismantle unless you take time to ask questions.

In a meeting with a group of executives recently, I was asked; what questions do you ask? How do you start the process? (They placed the emphasis on you).

I reminded them that it starts with what they already know how to do, but often overlooked in the heat of the moment. You start by asking the people involved in the conflict to define the key issues, even to the point of defining keywords so that there is a common understanding of what the words and phrases mean.

Dr. Ichak Adizes of the Adizes Institute makes a similar point in one of his recent articles where he wrote that “they must first agree on what they are talking about before they can discuss it or disagree. Once we define what we mean by the words we use, once everyone involved knows what they are talking about, it is much easier to resolve conflict.”

This all part of step one where the leader or the person guiding the negotiation creates distance between the people and the issues being disputed. Once you establish common ground between and among the parties, it is possible to move to the next step in the process.

Conflict resolution is a process and there is no getting around that. Skip a step and you run the risk of having it come apart where one of two things can happen.

You have to start all over, and this generally means the process will take longer because there will be a loss of credibility to be overcome, or the conflict escalates and the ability to resolve the issues without outside help becomes that much more difficult.

Where the process is followed and none of the steps are missed or skipped, the second part of the process – constructing the explanation – is easier to achieve. By using the agreed to definitions and meanings, the explanation of the issues becomes a bi-lateral part of the process and reinforces the notion that looking at alternatives is an acceptable course of action by those involved in the conflict.

One of the people in the meeting I referred to above said that he typically did not want to hear explanations for what went wrong and that too many times he hears more about that than he wants or needs. I agreed with him that unless they are at a lessons learned stage, talking about why something happened is not constructive to conflict resolution.

Yet, sometimes a little patience goes a long way and if the leader allows the parties involved in the conflict to vent a little bit (separately), it will sometimes clear the air enough to allow them to move to the next step. But if that time is allowed, it should be brief, and the parties to the conflict brought back to focus on the process.

The step in the process where the parties construct the explanation sets the stage for identifying the criteria that will be used to measure what is ultimately agreed to. The predicate for this is getting the parties to the conflict to agree that any criteria agreed to must be objective and measurable, and consist of elements on which an agreement or a decision can be reached.

The criteria become easier to define when the questions and the answers focus on what can be controlled and what can be changed. What are the actions needed, and who will take action on what needs doing? When it comes to change, it is often behavior that has to change, and the first person to accept that his or her behavior has to change, and acts on that need for change; that person will be seen as leading the way.

It is important to remember that, in a negotiation, being right can hinder rather than help.

What are you doing to prevent conflict in the workplace? If you don’t think you are doing enough, please call us. We have the skills and the techniques to train your senior leaders, and your managers and supervisors.

Food for Thought: “Being willing to change allows you to move from a point of view to a viewing point – a higher, more expansive place, from which you can see both sides”. (Thomas Crum)

I belong to a business cooperative called the Services Cooperative Association (SCA) whose mission is to help individuals start and build businesses.

I invite you to visit us any Wednesday morning at the Marriott Hotel in the Westchase District at 2900 Briar Park Drive. We start promptly at 7:30 AM and conclude at 8:30 AM. You can learn more about SCA at www.servicesca.org.

Get In Touch

(832)-452-8537

(281)-861-4947

jerry@cdci-mediation.com